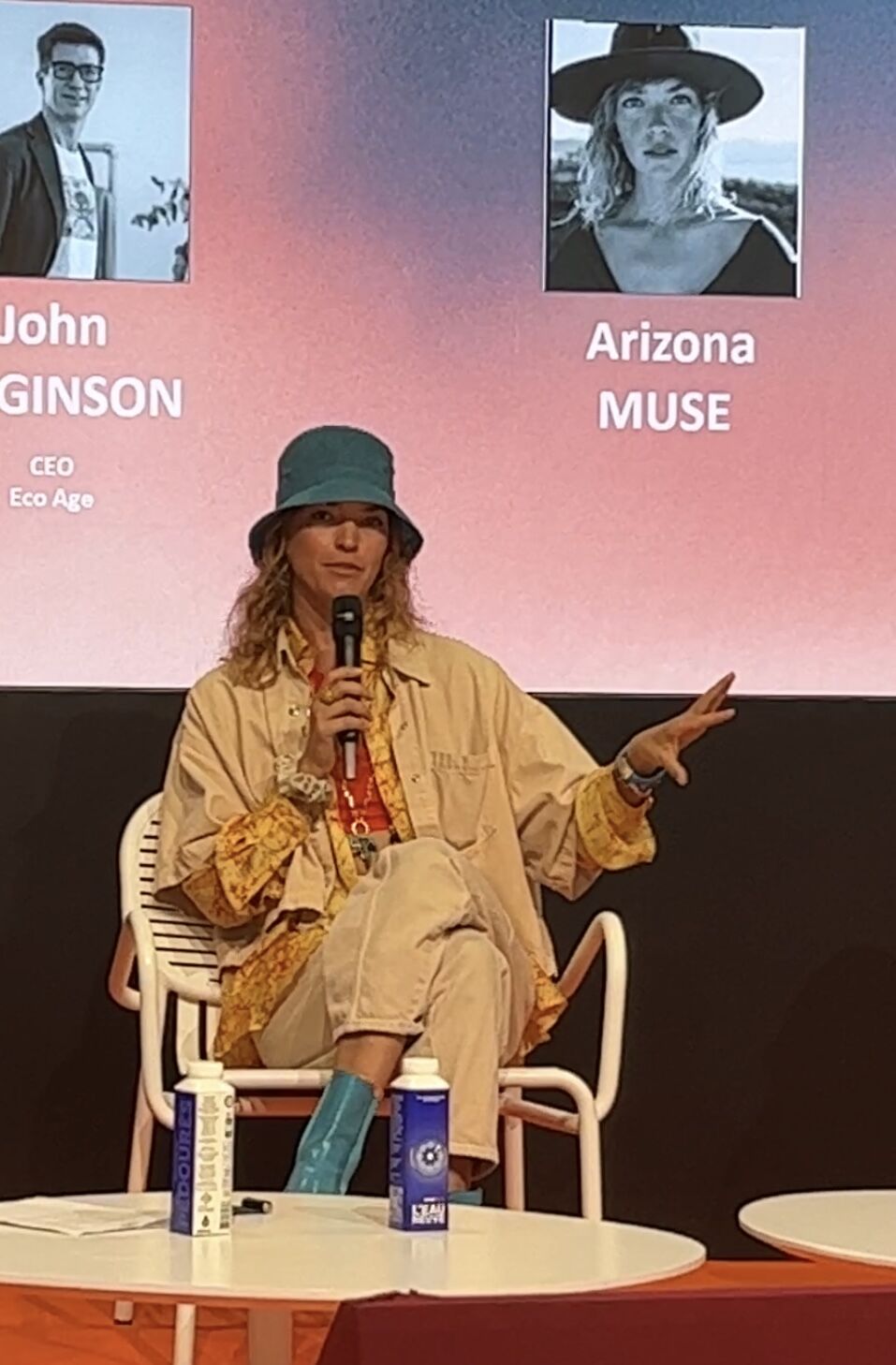

“We need to make fashion for worms. Fashion that can decompose in the soil.” When Arizona Muse, model and environmental activist, delivered this provocative line at Première Vision Paris, she wasn’t being poetic. She was crystallizing fashion’s most pressing contradiction, an industry that dreams of sustainability but remains shackled to the economics of convenience.

In 2025, the global fashion sector finds itself in a peculiar state of duality. On one hand, it’s bursting with innovation bioplastics, enzymatic recycling, regenerative materials. On the other, it’s suffocating under its own addiction to cheap polyester and fast cycles of consumption. The tension between progress and affordability has never been starker.

The polyester paradox

At the heart of the debate lies polyester, the fossil-fuel-based fiber that has come to define modern clothing. It is cheap, durable, and adaptable and it accounts for more than half of all fibers used in apparel today. Yet, as Arnaud Brunois-Gavard, Sustainability Manager at ECOPEL | Faux Fur Artisan, admits, breaking free from polyester is no easy feat. His company’s latest innovation, Biofur, a plant-based faux fur made from fermented corn sugar (PLA) embodies the future of circular fashion. But demand tells a different story.

“Despite the new material we offer, the client orders our polyester products,” he laments. It’s not a lack of innovation holding the industry back its economics. Polyester remains far cheaper than its eco-friendly counterparts, and with cotton prices surging due to erratic harvests, the dominance of synthetics is only deepening.

The new frontier, enzymatic recycling

Yet, innovation persists. On the trade fair floor in Paris, amid rows of recycled textiles and organic yarns, one breakthrough stood out: enzymatic recycling. Unlike mechanical or chemical recycling, which degrade material quality, enzymatic recycling breaks down polyester to its molecular core allowing it to be reconstituted into virgin-quality fiber. “This enables infinite recycling of polyester,” explains Greta Edkvist, Brand Manager at Chinese company Reo-Eco. “In theory, it can eliminate the need for new raw materials altogether.” If scaled successfully, enzymatic recycling could make synthetic fibers circular transforming plastic fashion into a resource loop rather than a waste stream. But in theory is doing heavy lifting.

Infrastructure, the missing link

The grand promise of a circular economy falters without one critical component collection and sorting infrastructure. Across much of Europe and Asia, textile waste systems are disjointed, underfunded, or nonexistent. Moreover, ultra-fast fashion has worsened the problem. The flood of cheap, blended fabrics produced by global giants makes recycling nearly impossible. The materials are too low in quality and too complex in composition for most recycling technologies to process. “You can’t close the loop if what’s inside it keeps breaking,” says a sustainability analyst at the event. This broken loop is emblematic of fashion’s circular challenge a system built for speed and scale now struggling to retrofit sustainability onto a model designed for disposability.

The consumer conundrum

And then there’s the consumer, the final, decisive link in the chain. A recycled wool fleece priced at €300 competes with a polyester version sold for €30. For most, the decision isn’t moral; it’s mathematical. “People talk about sustainability, but their wallets still vote for convenience,” opines an European retailer notes. This green hypocrisy, consumers advocating eco-consciousness while shopping for the cheapest option, results in the paradox. Sustainability cannot thrive on rhetoric alone. As one industry observer put it, “We need consumers who not only talk about green fashion but buy it. Otherwise, innovation will remain a showcase, not a solution.”

From greenwashing to ground truth

The industry’s shift toward circularity also demands honesty from both brands and buyers. Greenwashing has diluted public trust, as labels tout eco-friendly collections that merely offset, rather than overhaul, unsustainable practices. True change, experts say, will require transparency from brands and patience from consumers. Circular materials and enzymatic recycling can make fashion renewable but only if the market rewards such efforts.

Fashion for worms and humans

Arizona Muse’s phrase ‘fashion for worms’ isn’t just a metaphor. It’s a manifesto for transformation. To make biodegradable fashion mainstream, every link in the supply chain must evolve: from innovators creating compostable fabrics to governments investing in textile recycling, and consumers choosing products that outlast trends rather than landfill lifespans.

Fashion’s next revolution won’t be defined by color palettes or hemlines but by chemistry, ethics, and economics. The path to ‘fashion for worms’, might just begin when the industry and customers decide that the price of progress is worth paying.