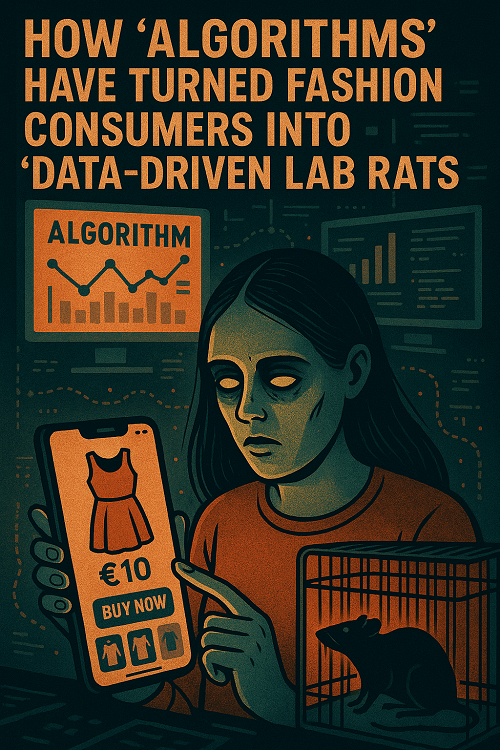

There's a quiet irony nestled in the acronym "EPR," Extended Producer Responsibility. A term that once evoked accountability and systemic transformation is now, paradoxically, in danger of becoming a rhetorical fig leaf, concealing the continued displacement of responsibility from industry to individual. Latest research from WEFT, investigating consumer tolerance for visible EPR charges on clothing in the UK, deserves attention not only for its findings but more so for what those findings quietly endorse: a consumer-funded vision of sustainability.

If a ‘producer responsibility’ framework results in consumers paying an extra $0.50 or $1.00 at checkout to fund the cleanup of the industry’s mess, then something fundamental has been inverted. Producer responsibility, once the ethical bedrock of sustainable industry reform, is being re-engineered into consumer responsibility, taxed by another name.

The great inversion, from producer to payer

The concept of Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR), first formalised in Sweden in the early 1990s, was revolutionary. It aimed to shift the financial and physical burden of waste management from municipalities and taxpayers directly to the producers of goods. The underlying principle was clear: the polluter pays, and in doing so, is incentivised to design products that are more durable, recyclable, and ultimately less impactful on the environment. It was about internalising externalities – making the true cost of production visible and accountable.

However, the WEFT report suggests a subtle but significant mutation of this principle. Around 80 per cent of the 1,762 surveyed UK shoppers supported a visible charge if its purpose was explained clearly. Transparency, after all, builds trust. But this acceptance is being dangerously misinterpreted as consent to transfer the financial burden of environmental repair from corporations to the very people buying their products.

Imagine going to a restaurant where, after ordering your meal, you’re told that you must pay a separate “kitchen hygiene fee” or a “waste disposal charge.” One might reasonably ask: Shouldn’t cleanliness and responsible waste management be the inherent responsibility of the establishment, not an à la carte ethical extra? This is precisely the absurdity we’re entertaining with the customer paying the EPR fees directly and visibly. The industry’s mess, now conveniently labelled ‘EPR,’ is being passed on as a consumer’s problem to fund.

The data dilemma, a mountain of waste

The textile industry, in particular, is a prime candidate for strong EPR. Its environmental footprint is staggering, from water consumption and chemical use in production to the colossal waste generated at end-of-life. The scale of the problem underscores why true producer responsibility is so critical:

Table: EPR, the shifting sands of responsibility

|

Metric |

Value (Approx.) |

Context/Source |

|

UK Textile Waste to Landfill |

350,000 tonnes/year |

Environmental Audit Committee, House of Commons |

|

Global Textile Waste (2030 est.) |

148 million tonnes |

World Bank / Ellen MacArthur Foundation |

|

Clothing Recycled into New Clothing |

<1% (globally) |

Ellen MacArthur Foundation |

|

Average wears per garment (fast fashion) |

~7-10 times |

Various reports, declining trend |

|

Microplastic pollution from textiles |

Significant contributor |

Numerous scientific studies |

With less than 1 per cent of materials from clothing recycled into new clothing globally, the current linear model is unsustainable. The problem demands systemic change, not simply a new revenue stream for existing industry practices.

Who really pays?

EPR schemes exist globally in various forms, but their effectiveness often hinges on how strictly the "producer pays" principle is upheld:

German Packaging EPR (Green Dot): Germany pioneered financial EPR for packaging. Producers pay a fee based on the weight and material of their packaging to a "dual system" (e.g., Green Dot) responsible for collecting, sorting, and recycling. While these costs are inevitably factored into product prices, the responsibility for funding and managing the recycling infrastructure lies firmly with the producers and their collective schemes. It incentivizes them to reduce packaging or choose recyclable materials to lower their fees. The consumer doesn't see a separate line item, but the system is robust.

Proposed EU textile EPR: The European Union is moving towards mandatory EPR for textiles by 2025. The aim is to make producers financially responsible for the collection, sorting, and recycling of textile waste. The critical question, however, remains: how much of this cost will truly be absorbed by producers through design changes and efficiency, and how much will be passed directly or indirectly to consumers? The UK's WEFT report reflects this ongoing tension – a proactive move to gauge consumer willingness to bear a visible cost, potentially before the full implications of producer obligations are felt.

The concern arises when the EPR charge, instead of driving fundamental shifts in production, becomes a mere pass-through mechanism. If my £1 EPR charge is being used to fund a system that transforms cotton garments—known for their versatility, biodegradability, and renewability—into chemically intensive and industrially dependent alternatives like recycled viscose or lyocell, then as a consumer I would rather keep that £1. Or better yet, choose where it goes. This isn't about fostering true circularity; it's about funding the industry's preferred (and often most profitable) recycling routes, even if they aren't the most environmentally sound or aligned with consumer values.

A sustainability tax, not EPR

Currently, sustainability is being repackaged as something consumers must purchase rather than something producers must embed. The EPR charge becomes yet another toll booth on the ethical shopping highway, inviting consumers to feel virtuous while corporations continue to externalize the true costs of doing business. This dilutes the very essence of producer responsibility, shifting the onus of environmental repair from the creators of the mess to the end-users.

If the industry wants to pass a fee onto the consumer, that is fine. But do not dress it up as EPR. Call it what it is: a sustainability tax. And if that is the path we choose, we should at least ensure it is spent on the most critical, community-driven, and systemic interventions. This includes investing in local repair economies, supporting genuine closed-loop material innovation, fostering better collection infrastructure that prioritizes reuse, and crucially, incentivising producers to design products that last longer and are easier to recycle mechanically.

In the end, the test of any EPR scheme is simple: who bears the cost, and who reaps the benefits? If we cannot answer this clearly and justly, then perhaps it’s time to return to first principles. Let us remember that producer responsibility must begin and end with the producers. Only then can EPR truly live up to its name and deliver the systemic transformation our planet desperately needs, rather than becoming another burden on the unwitting consumer.