Europe prides itself on being a leader in sustainability, but ironically, its textile recycling sector is on the verge of collapse. This critical industry is struggling under the weight of policy inertia, economic unsustainability, and severe structural fragmentation. A recent visit by EU Commissioner Jessika Roswall to the Evadam sorting plant, part of the Boer Group, highlighted a reality: the ambitious vision of a textile-to-textile recycling system is dangerously close to unraveling. Yet, symbolism alone won't rescue an industry teetering on the brink.

The disconnect of legislation vs. operational reality

European textile recyclers are caught in a paradoxical bind. They are expected to build a robust circular ecosystem, but without the essential policy framework or financial incentives to do so. While mandatory separate collection of post-consumer textiles began across the EU in 2025, crucial legislation for minimum recycled content or harmonized Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) remains pending. This gap means recyclers are collecting more textiles than ever, but lack sustainable—or profitable—outlets for them.

The high cost of policy gaps

The struggles of major players in the textile recycling sector underscore the urgent need for systemic change.

Sweden’s Renewcell: From market darling to bankruptcy

Renewcell, once hailed as a pioneer in textile-to-textile recycling with its patented Circulose pulp, filed for bankruptcy in February 2024. Despite a Nasdaq listing in 2020 and partnerships with major brands like H&M and Levi’s, the company could not secure consistent feedstock or sufficient offtake commitments to remain viable.

Table: Renewcell’s losses

|

Metric |

2022 |

2023 |

|

Revenues (€ million) |

10.1 |

15.3 |

|

Net Loss (€ million) |

-23.2 |

-28.5 |

|

Factory Utilization |

40% |

<30% |

"We built a world-class factory. What we lacked was a world that was ready to use it." — Patrik Lundström, former CEO, Renewcell. The core issue: despite initial buzz, brands failed to commit to regular offtake agreements, leaving the plant underutilized and financially unsustainable.

Germany’s Soex shrinking in silence

Soex Group, one of Europe’s largest textile sorters and recyclers, has quietly scaled down operations in multiple countries over the past two years. This is primarily due to rising costs and tightening margins. While not bankrupt, the group has halted planned expansions, citing a lack of regulatory clarity and falling resale values of used garments. As a Soex executive points out, without predictable legislation and incentives for fiber-to-fiber innovation, they can't justify capex.

Table: Soex groups falling investments

|

Area |

Planned Investment |

Status |

|

Spain (2022) |

€12 million |

Cancelled |

|

Romania (2023) |

€8 million |

Delayed indefinitely |

|

Poland (Sorting Hub) |

€6 million |

Scaled back by 60% |

Cheap fashion or system failure? A false binary

Much public and policy ire has landed on Chinese ultra-fast fashion giants like Shein and Temu. Their ultra-low-cost, high-turnover products have flooded the EU market, raising concerns about overconsumption and waste. But critics argue this focus oversimplifies the problem. European brands, too, have long relied on low-cost overseas manufacturing and design garments with little regard for recyclability. "Blaming imports ignores a homegrown crisis: we don’t value durability, and we’ve never built an infrastructure to support circularity," said a sustainability analyst with the European Environmental Bureau.

No business model, no future

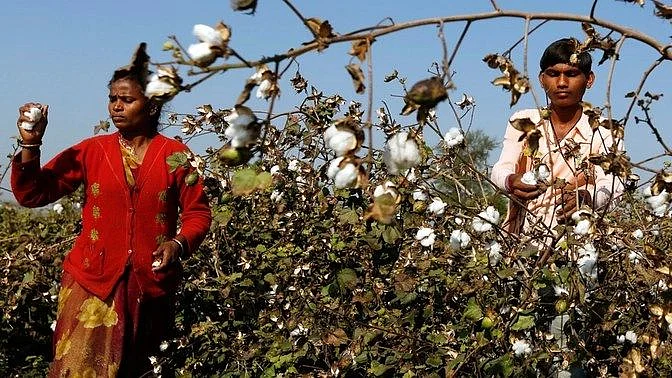

Beyond blame, the core challenge remains brutally economic. Most collected textiles are chemically treated, made of mixed fibers (like cotton-poly blends), or embedded with elastane, making fiber recovery expensive and technologically complex. Virgin fibers remain cheaper, especially in the absence of regulatory pressure to change.

|

Challenge |

Impact on Viability |

|

Mixed fiber composition (e.g., cotton-poly blends) |

Low recyclability, high processing cost |

|

Contamination from dyes & elastane |

Blocks high-value recovery |

|

Low resale value of used clothing |

Erodes profitability of sorting |

Policy paralysis, fragmented and faltering

Europe's textile recyclers are currently navigating a policy swamp, with inconsistent rules and patchwork regulation from one country to another. “What we need is policy that matches ambition—not just in words, but in enforceable rules and incentives,” said a policymaker from DG Environment.

Table: EU policies

|

Area |

Status |

Comment |

|

EPR (EU-wide harmonization) |

Pending |

27 different national systems persist, leading to fragmentation |

|

Minimum Recycled Content Mandate |

Not yet enforced |

Pledged but implementation is lagging |

|

VAT exemption on secondhand clothing |

Still under discussion |

Could stimulate reuse but faces opposition from fiscal authorities |

|

Eco-modulation of fees |

Uneven |

Only a few member states link fees to product sustainability |

From crisis to opportunity

For textile recycling to become a cornerstone of Europe's green economy, a fundamental systemic shift is required, not merely symbolic gestures.

Design for circularity: Mandate circular product design (e.g., mono-fibers, no elastane, removable trims) by 2028. If garments cannot be easily recycled, they should not be sold.

Link EPR to real infrastructure: Require EPR funds to be directed specifically to approved recyclers. Mandate long-term procurement contracts between brands and recyclers to ensure stable feedstock and demand.

Replace trade barriers with innovation grants: Instead of high import tariffs, offer EU-wide grants or low-interest loans to Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs) focused on automated sorting, chemical recycling, and closed-loop fiber technologies.

True cost accounting: Develop consumer-facing labels that display the "true cost" of fashion, including carbon footprint, water usage, and recyclability index, to encourage responsible consumption.

Europe’s choice, collapse or breakthrough?

Thus the European textile recycling industry's struggles are not due to a lack of intent but rather a severe structural misalignment between policy, economics, and technology. The downfall of pioneers like Renewcell proves that vision alone is insufficient.

Europe now faces a critical choice: lead with decisive action or risk languishing in paralysis, watching vital infrastructure erode while legislation lags. As Commissioner Roswall’s visit underscored, the crisis is undeniable. However, this moment of crisis could also serve as the catalyst for transformative change. The future of circular fashion in Europe hinges not on assigning blame, but on bold, grounded, and collaborative reform.