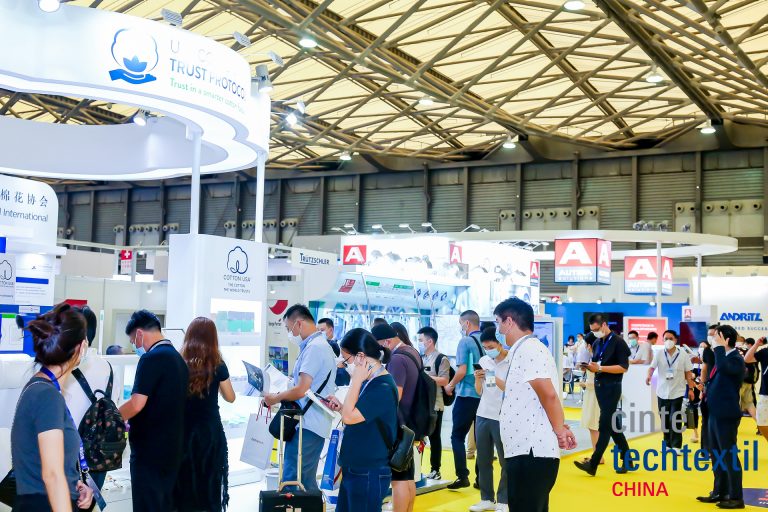

India has moved decisively to restrict fabric imports from Bangladesh, enforcing a port-only policy that bars overland entry of key jute and textile materials. In a fresh notification issued by the Directorate General of Foreign Trade (DGFT), New Delhi declared that specific shipments—including jute products, flax tow, jute yarns, and woven fabrics—will now be allowed entry solely through the Nhava Sheva port in Maharashtra. Effective immediately, the measure is being hailed domestically as a protective step for India's struggling textile sector but is drawing ire in Dhaka as a sign of deepening economic hostility.

The move signals the continuation of a tit-for-tat trade spiral that has escalated sharply since April 2025, when India first withdrew transshipment privileges for Bangladeshi exports to third countries. That was followed by restrictions in May on processed food and ready-made garment (RMG) imports. Now, with the jute segment under the scanner, the fault lines in Indo-Bangladesh trade relations are fully exposed.

What the restriction entails

As per the DGFT's new guidelines, imports of the affected categories are now barred from entering India through any of the land customs stations along the India-Bangladesh border. This includes critical transit points like Petrapole and Benapole, which have long served as commercial arteries between the two neighbours. The only exception: Bangladeshi goods transiting through India en route to Nepal and Bhutan will still be permitted. However, re-exports from these countries back into India have been explicitly prohibited—a clause designed to thwart alleged third-country circumvention tactics.

Trade disruption or domestic revival?

The decision comes with both economic risks and political rewards. Bangladeshi exporters, especially in the RMG and jute segments, will face longer delivery cycles and increased freight costs. Previously, land shipments to India could arrive within 3–4 days. Now, with ocean transit through Nhava Sheva, the wait time stretches to 7–10 days or more.

For Indian retailers and consumers, this could translate into a 2–3 per cent price uptick for winter apparel like T-shirts, jackets, and jeans, especially if the disrupted flow persists into the festival season. But for India’s domestic textile manufacturers—particularly those in jute and cotton weaving hubs—the shift is a potential lifeline.

“This move plugs a significant policy loophole. It not only addresses dumping concerns but helps channel demand back to Indian mills,” says Rajat Mehta, Director, Eastern Textiles Association. “We anticipate a Rs 1,500 crore uptick in capacity utilization by mid-2026 if these measures hold.”

The government, too, is framing this within the larger Atmanirbhar Bharat (self-reliant India) campaign. By stemming the flow of low-cost or allegedly subsidized Bangladeshi imports, it aims to give Indian producers a much-needed competitive edge.

Table : India-Bangladesh trade March 2025

|

Category |

India's exports to Bangladesh ($) |

India's imports from Bangladesh ($) |

|

Total Trade |

$973M |

$171M |

|

Top Indian Exports |

||

|

Cotton Yarn |

$150M |

|

|

Rice (Other Than Basmati) |

$116M |

|

|

Petroleum Products |

$58M |

|

|

Top Bangladeshi Exports |

||

|

RMG (Cotton & Accessories) |

$34.7M |

|

|

Footwear (Leather) |

$14.7M |

|

|

RMG (Other Textile Material) |

$12.3M |

Source: The Observatory of Economic Complexity (OEC), March 2025 data

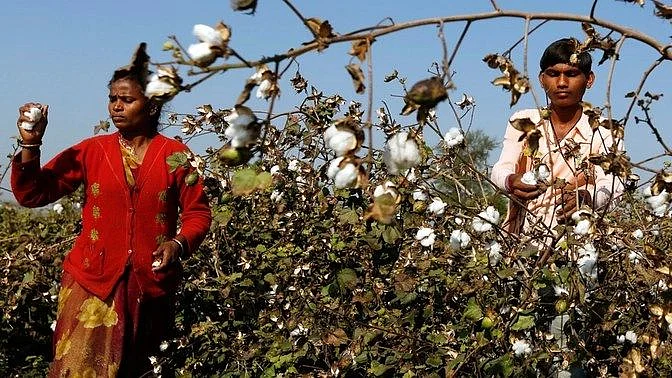

Unequal trade and the jute flashpoint

Underlying the policy move is a long-simmering grievance: the fate of India’s jute industry. While Bangladesh has built a robust export ecosystem around jute—thanks to subsidies and duty-free access under the South Asian Free Trade Area (SAFTA)—India's jute producers have struggled with falling prices, unpaid dues, and frequent mill shutdowns. “Our farmers are losing out due to under-invoiced and low-grade jute flooding Indian markets,” said Pradeep Saha, a jute grower from Murshidabad, West Bengal. “Government MSP means little when imported jute is sold at below cost.”

India alleges that Bangladesh's jute exports are subsidized and occasionally mislabeled to avoid existing anti-dumping duties. The port-only restriction is intended not just to control volumes but also to enable more thorough quality inspections and prevent regulatory evasion.

Table: India’s jute & textile bast fibre imports from Bangladesh

|

Fiscal year |

Value ($ mn) |

|

FY2017 |

138 |

|

FY2022 |

117 |

|

FY2024 |

144 |

|

2024 |

87.18 (Annualized) |

An eye for an eye: reciprocal restrictions

This hardening of India’s stance coincides with regulatory steps by the Bangladeshi interim administration under Muhammad Yunus, which has blocked Indian yarn and rice exports through land ports, citing the need to shield its own farmers and weavers. Bilateral trade, while still significant at nearly $13 billion, is increasingly marked by protectionism and friction.

“There’s a risk of long-term economic decoupling,” warned Prof. Nusrat Rahman of Dhaka University’s Centre for Trade Policy. “If both sides continue to weaponize trade policy, informal markets may surge and regional economic cooperation will suffer.”

The road ahead

India’s decision to reroute Bangladeshi fabric imports exclusively through Nhava Sheva port may fulfill short-term domestic goals, but it raises broader questions about regional economic integration and diplomatic tact. The impact will reverberate through textile supply chains, price-sensitive retail segments, and border economies where cross-border trade is a livelihood, not just a statistic.

As both nations dig into protectionist positions, a constructive dialogue—perhaps through SAARC or BIMSTEC—may be the only way to prevent economic rivalry from becoming a full-fledged trade war. Until then, fabric isn’t the only thing under strain; so is the very fabric of bilateral trust.