The air in numerous pockets of the country hangs thick with the stench of discarded refuse, a stark testament to a system teetering on the brink of its own waste. Mountains of discarded plastic choke landfills from Mumbai to Chennai, leaching toxins into the soil and water. The insatiable hunger for raw materials continues to strip our planet bare, driving deforestation and resource depletion. We label this a ‘waste problem’ yet the overflowing bins and environmental degradation are increasingly recognized as symptoms of a far more fundamental flaw: the very design of the products we consume.

The cold, hard numbers paint a damning picture. As per Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Globally, an estimated 1.3 billion tonnes of food are lost or wasted annually. Closer home, India grapples with its own immense food waste, contributing significantly to environmental and economic losses. Our personal vehicles, status symbols and essential tools, remain parked for an astounding 92 per cent of the time, representing a massive underutilization of resources and embodied energy. Consider the humble drill: studies in Europe have shown an average usage of just 12-13 minutes over its entire lifespan, lying dormant in sheds and garages, a monument to infrequent need and a linear consumption model.

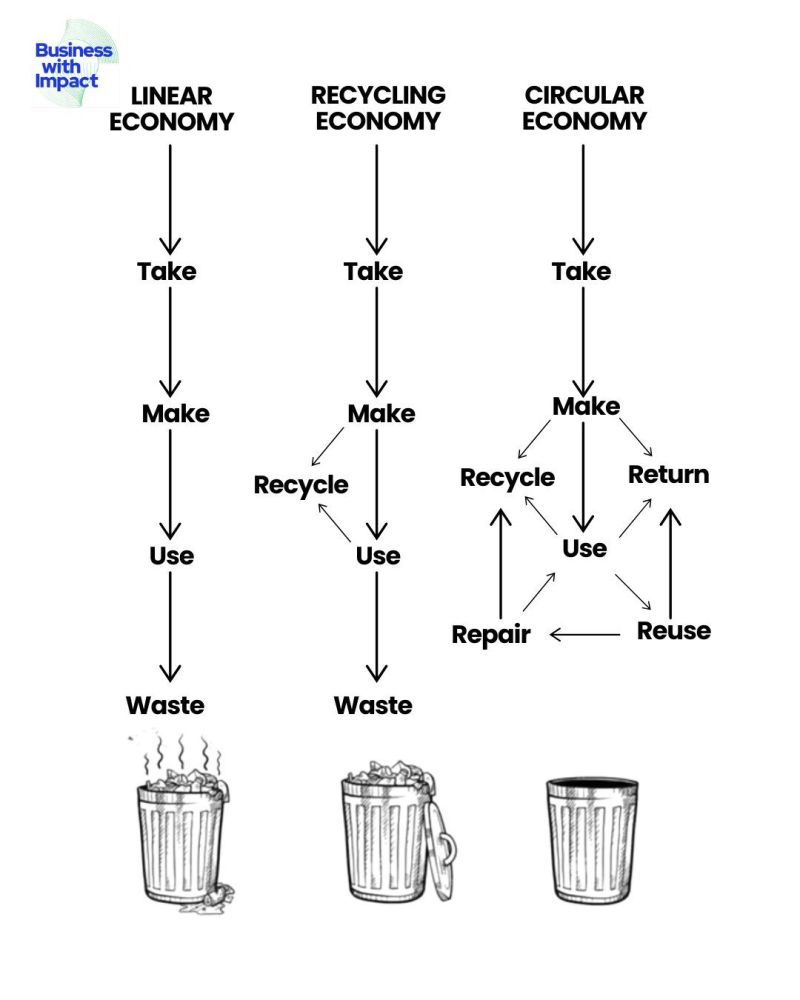

Where does this all end up? The answer, as the attached image grimly illustrates, is the landfill. Our dominant economic paradigm, the Linear Economy, operates on a disturbingly simple, and ultimately unsustainable, principle: Take → Make → Use → Waste. It's a one-way street with a dead end, a system that inherently treats the Earth's resources as infinite and its capacity to absorb waste as boundless. The visual representation of overflowing garbage bins serves as a potent symbol of our collective failure to account for the long-term repercussions of our consumption patterns.

The promise of ‘recycling’ as a panacea for our waste woes offers a mere illusion of a solution. While undeniably a necessary component of a more sustainable future, the "Recycling Economy" depicted still culminates in waste. It's a system of temporary reprieve, a detour on the inevitable journey to disposal. Globally, only an estimated 9 per cent of all plastic waste ever produced has been recycled (UN Environment Programme, 2018). The energy and resources invested in the recycling process itself, coupled with the limitations of current recycling technologies and the contamination of waste streams, mean that it cannot be the sole answer to our escalating waste crisis.

The inconvenient truth, increasingly echoed by scientists, economists, and environmentalists, is that we don’t have a waste problem — we have a design problem. Products are frequently conceived with planned obsolescence embedded within them, intentionally engineered to become outdated, malfunction, or fall out of fashion, thereby leading to a cycle of continuous consumption. This isn't merely an environmental oversight; it's a fundamental flaw in a system that appears to have developed amnesia, tragically forgetting the basic ecological principle that every "end user" inhabits the same finite planet. This ‘capitalism with amnesia’ as critics incisively label it, prioritizes short-term profit margins over the long-term well-being of both the environment and society.

However, a viable and increasingly compelling alternative exists, a model that isn't radical but rather, as the image powerfully suggests, common sense imbued with a survival instinct: the Circular Economy. This transformative paradigm reimagines our relationship with resources, breaking free from the linear "take-make-dispose" model and embracing a closed-loop system. Its core principles are elegantly simple and profoundly impactful: Take → Make → Use → Reuse → Repair → Return → Recycle. And crucially, repeat. Over and over again, creating a regenerative system where waste is minimized and resources are kept in circulation for as long as possible.

Imagine a world where smartphones are designed with easily replaceable batteries and modular components, extending their lifespan and reducing electronic waste. Picture clothing designed for durability and made from recyclable materials, with manufacturers offering take-back schemes to close the loop. This isn't a distant utopia; it's a tangible future being built by innovative businesses and forward-thinking policymakers.

The benefits of transitioning to a circular economy extend far beyond mere environmental responsibility. For businesses, this shift unlocks a wealth of opportunities and tangible advantages:

Fewer raw materials = lower costs: By designing products for longevity, reuse, and remanufacturing, the demand for virgin resources diminishes significantly, leading to substantial cost savings and greater resource independence. For example, Renault's remanufacturing plant in Flins, France, reconditions engines, gearboxes, and other vehicle parts, achieving cost savings of up to 50 per cent compared to producing new parts.

Longer product lifecycles = more value: Durable and repairable products retain their value for longer, fostering stronger customer relationships built on trust and longevity. This can also pave the way for innovative business models centered around leasing, sharing platforms, and performance-based contracts, shifting the focus from selling products to providing services. Consider the success of companies offering "lighting as a service," where customers pay for illumination rather than owning light bulbs, incentivizing manufacturers to produce long-lasting, energy-efficient products.

Built-in sustainability = more customer loyalty: In an increasingly environmentally conscious world, businesses that demonstrably prioritize sustainability attract and retain customers who align with these values. A Nielsen study found that 66 per cent of global consumers are willing to pay more for sustainable brands. Integrating circular principles into product design and business operations becomes a powerful differentiator and a driver of brand loyalty.

The growing "right to repair" movement, gaining momentum globally and in India, underscores the public's dissatisfaction with planned obsolescence. Consumers are demanding access to the necessary parts, tools, and information to repair their own devices, pushing back against manufacturers who deliberately restrict repairability. This isn't just about saving money; it's a fundamental assertion of ownership and a rejection of a system designed for premature disposal.

Furthermore, inspiring case studies demonstrate the real-world viability of circular business models:

• Patagonia: This outdoor clothing company is renowned for its commitment to durability, repairability, and recycling. Their "Worn Wear" program encourages customers to repair and reuse their gear, offering repair services and selling used Patagonia products, effectively extending product lifecycles and reducing waste.

• Fairphone: This Dutch company designs and manufactures modular smartphones that are easier to repair and upgrade, challenging the industry's trend of disposable electronics. Their focus on ethical sourcing and product longevity provides a compelling alternative for conscious consumers.

• Interface: This global flooring company has embarked on a "Mission Zero" to eliminate any negative environmental impact by 2020 (and is now pursuing "Climate Take Back"). They have pioneered innovative approaches to material sourcing, product take-back, and closed-loop recycling in the carpet industry.

Table: Comparative product lifecycle across various economic models

|

Feature |

Linear Economy |

Recycling Economy |

Circular Economy |

|

Resource Use |

High reliance on virgin resources |

Reduced reliance, but still significant |

Minimal reliance on virgin resources |

|

Product Design |

Often designed for obsolescence |

Design for function, less focus on end-of-life |

Design for durability, repair, reuse, and recyclability |

|

Waste Generation |

High waste at end-of-life |

Reduced waste, but still present |

Minimal waste, resources kept in loop |

|

Value Retention |

Value lost at end-of-life |

Some value recovered through recycling |

High value retention through reuse, repair, remanufacturing |

|

Economic Model |

Primarily focused on sales of new products |

Includes recycling as an end-of-life process |

Emphasizes service models, product longevity, and resource efficiency |

|

Environmental Impact |

High resource depletion, high pollution |

Lower than linear, but still significant |

Significantly lower resource depletion and pollution |

The transition to a circular economy is not merely an environmental imperative; it is an economic opportunity. It demands a fundamental shift in design thinking, manufacturing processes, consumer behavior, and supportive government policies. It necessitates collaboration across industries, from material producers to product designers to waste management companies, and a collective willingness to embrace innovation and long-term thinking.

The image highlights a clear and critical choice: persist on the linear path towards an overflowing bin, a metaphor for a system choking on its own excesses, or embrace the cyclical wisdom of a circular economy, where resources are cherished, products are engineered for longevity, and waste is minimized by design. The future of our planet, the resilience of our economies, and the well-being of generations to come hinge on the choices we make today. The time for "common sense with a survival instinct" is not just approaching – it is here.